Labyrinths Bridge Faith Traditions and Communities

Most religions use a form of prayer in their observances. The traditions vary widely, from silent, private communication to vocal prayers done with a group. Some Native Americans see dance as prayer, and the Sufi sect of Islam has adherents who whirl in beautiful meditations.

Prayer affects each person differently. Keith Earl, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, leads the Southern Dallas Interfaith Council. When Pastor Jane Griner of Trinity United Methodist Church came to the March meeting, she invited the group to her church’s May 4th labyrinth walk. Keith wasn’t familiar with the tradition but looked forward to attending. Afterward, he said, “I had a revelatory experience as I walked the labyrinth. Things came to my mind about my business and my future plans that I wasn’t expecting.” Another walker said, “It works—I just don’t know how.”

International Labyrinth Day, , observed on May 4th at 1 p.m. local time worldwide, is a testament to the enduring significance of this ancient practice. Christians have been using labyrinths for meditation since the 4th century AD. These intricate pathways, often set within a circle, symbolize a journey to salvation or to Jerusalem. This historical and cultural context adds depth and richness to the practice of labyrinth walking, enlightening the reader about its origins and evolution.

The most famous labyrinth lies within the Chartres Cathedral near Paris. This church, distinguished by its towers built hundreds of years apart, also contains original stained glass windows. The labyrinth pattern is called unicursal, which is composed of a single continuous path within a circle.

The Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex is home to dozens of labyrinths. Their locations vary widely, from churches to homes to hospitals to senior living centers. Some are temporary—painted on canvas—and can be put down for special occasions. Most are outside, but some, like the one at Chartres, are inside a building. Besides Trinity UMC, the area has only one or two permanent indoor labyrinths.

Trinity United Methodist Church, tucked in a southern neighborhood of Duncanville, welcomed several dozen walkers to its indoor labyrinth on Saturday. The large room where it lies is almost bare except for two crosses, but the tile floor gleams. The pattern reflects the one at Chartres. Raymond Gager, a member of the congregation who is a master tile cutter, supervised the installation. The colors are simple and soothing: a white background with a sky-blue pattern. The workmanship is exceedingly careful and precise.

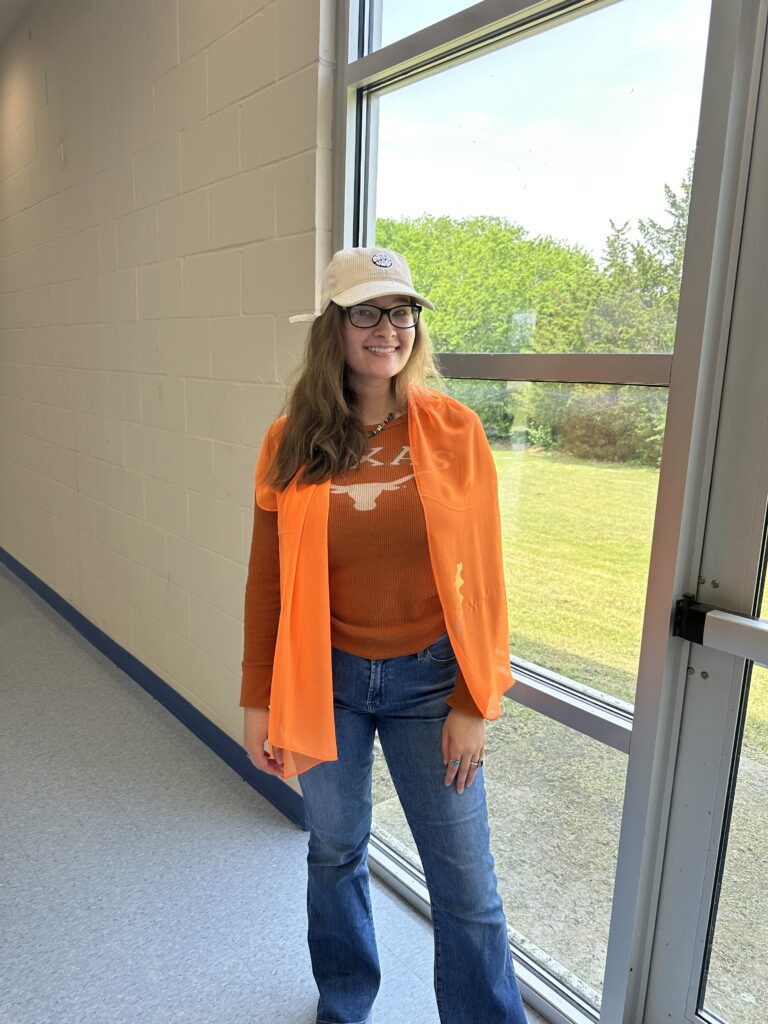

All ages were represented, coming from congregations near and far. One family with children came from Camp Wisdom United Methodist Church with their friend, Evelyn Glass. Emily Asunto is a University of Texas student graduating in May with a degree in sociology; her grandmother attends Trinity UMC. The Southern Dallas Interfaith Council members included Mae Nottingham, a niece of Tricia Harris from the Unity Church of Dallas. Mae reported a transformation from confusion to appreciation of being with the people in the group.

Kathy Norrod, a certified labyrinth facilitator, allayed the fears of those waiting to walk the labyrinth, “There isn’t a right way or a wrong way to do this.” She emphasized, “It’s not a maze. There aren’t any walls. If you need to leave, just walk out.” Her gentle encouragement helped those new to the experience, as did her well-informed insights. Kathy studied for over a year with Lauren Artress, the originator of the labyrinth renewal movement, before certification. Rev. Artress is an Episcopal priest who serves at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. This June, she will be at Chartres to host facilitator training.

Trinity UMC has had significant challenges in the last few years. Winter Storm Uri in 2021 caused massive damage when pipes broke, flooding the building with water. The labyrinth, originally built in 2003, had to be redone. The congregation had not been meeting for the year before because of COVID. Repairs from the water damage took until December 2021, when worshippers could return on a limited basis after two years of being away. Of particular importance, however, was that the plans for the labyrinth were not destroyed in the flood. Walter Wilcox, a well-known structural engineer, had designed the plan; he was the only member of Trinity lost to the virus. With his work, the meticulous cutting of the tile was possible.

Kathy Norrod loves to host visitors to the labyrinth by appointment. Trinity members are justifiably proud of their special installation. It is beautiful, but more importantly, it can literally restore walkers to the path of prayer.

Featured photo is Evelyn Glass, participating in International Labyrinth Day. Photo by Mary Ann Taylor.